How Fraudsters Steal Your Identity & Shop Online, Step by Step

a step-by-step walkthrough of a real order in our system, tracing how personal information first gets stolen, sold by middlemen and fraudsters, and used in a fraudulent order

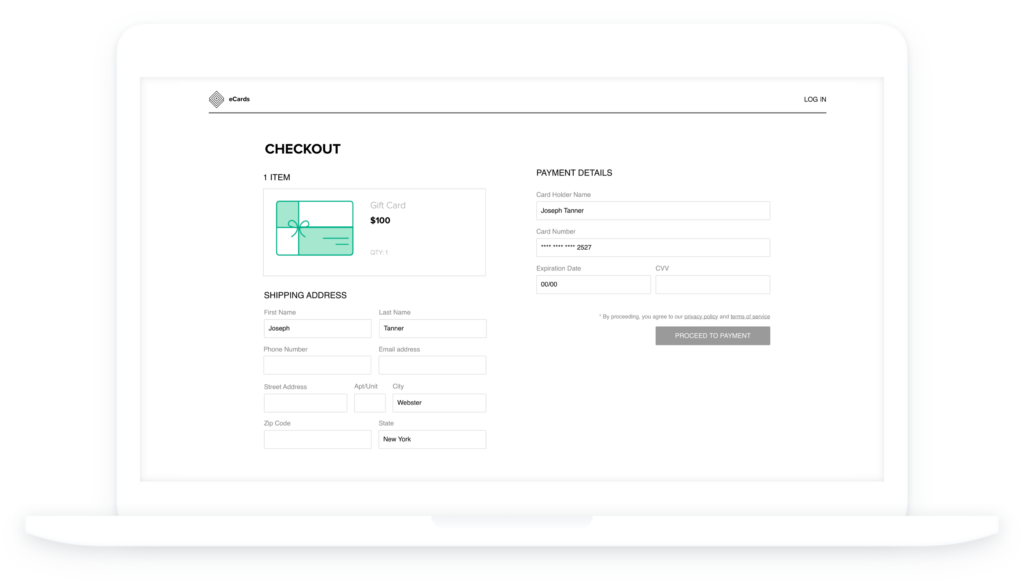

At 1:49 a.m. on the day before Thanksgiving in 2016, Joseph Tanner** ordered a $100 digital gift card at a digital gift card marketplace we’ll call eCards. It was to be delivered to Kasper Gleason at his gmx.com email address with a short message: “Hi.” Tanner paid for the item with a Bank of America Mastercard, the number ending in 2527 with a Webster, New York billing address.

Joseph placed the order through the Google Chrome web browser on his T-Mobile Android 6 phone, using a Seattle IP address. The same email address was used for both the sender and the recipient of the digital gift card – a common practice among those who prefer to print and hand-deliver the card details themselves. Perhaps Joseph, a New Yorker, was in Seattle for Thanksgiving doing last minute shopping as a surprise for his friend or relative, Kasper.

Neither was the case. Kasper Gleason was a fraudster using Tanner’s name, credit card number, and billing address to illegally buy the gift card. It’s been more than two years since Joseph Tanner’s name and card appeared in that first fraudulent order attempt in Riskified’s system, but these specific order details continue to have staying power. To this day we see fraudsters unsuccessfully use Tanner’s information across dozens of our merchants, sometimes multiple times per month! Just in 2019 alone, Tanner’s credentials were found in 44 new mentions across the dark web.

So how did Gleason – if that is his real name – first get his hands on Tanner’s personal information? How does someone steal your identity? How did Tanner’s personal information get circulated on the dark web? How did Gleason try to fool eCards into approving his order? How did eCards and Riskified stop these types of attacks? What can retailers and merchants do to protect themselves from eCommerce fraud?

Below is a step-by-step walk through of a real order in our system, tracing how personal information first gets stolen, sold by middlemen and fraudsters, and used in a fraudulent order with eCards. We will also focus on specific parts of cybercriminals’ nefarious processes. This blog post, brought to you in partnership with IntSights Cyber Intelligence, will also outline what retailers can do to weed out the illicit use of stolen credentials.

**All details have been anonymized to ensure cardholders’ privacy.

When did Tanner’s credit card first appear on the dark web?

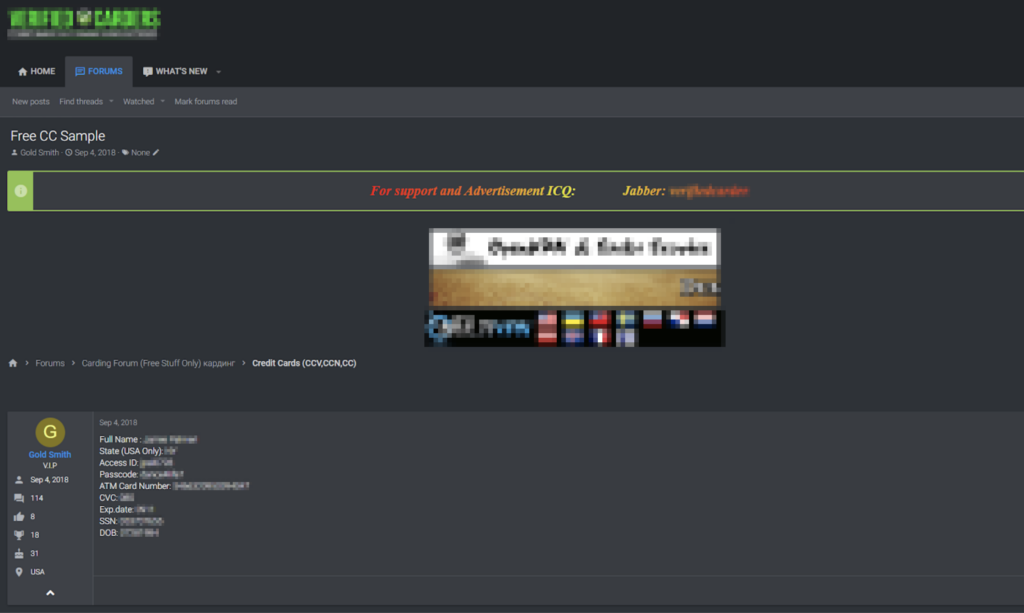

Joseph Tanner’s personal information and credit card credentials began appearing on multiple dark web forums in 2014. In a bit of bad luck, Tanner’s details are offered as a free sample for a bigger batch of stolen credit cards – a practice sellers use to prove themselves as legitimate vendors and the quality of their goods.

It’s nearly impossible to trace and pinpoint the exact moment when Tanner’s details were burgled. He could have swiped his card on a compromised gas pump, ATM, or point-of-sale device, where skimmers are installed to copy customers’ information from the magnetic strip or EMV chip. Someone could have stolen his bank statement off his porch or mailbox. Or what’s more likely is that his email account or account with the merchant’s mobile app or eCommerce website were compromised in a major hack or data breach that hit retailers, government organizations, financial institutions, and more.

Read more here on the lifecycle of stolen credit cards in the underground economy.

Indeed, the abundance of compromised card data and other assets available online continues to hinder the fight against card-not-present fraud. Despite many gains by law enforcement in recent years, card shops and other types of illicit marketplaces remain major facets of the underground economy and key enablers for CNP fraud. Card shops in particular have become the primary means through which fraudsters and cybercriminals obtain stolen payment-card data because they let fraudsters buy the stolen data without having to do so themselves. That lowers the barriers to entry for those with less-advanced capabilities or limited resources.

Data breaches have now become almost a fact of life. Hackers can grab your social security number, bank account number, as well as banking login information, literally within minutes. In 2018, the number of breaches surged to 1,244 per year from just 157 in 2005, according to Identity Theft Resource Center (ITRC). That means breach frequency has increased more than eight-fold in just over a decade. That’s why it’s no surprise that a significant amount, 39%, of fraud losses experienced by retailers – particularly mid- to large-sized mCommerce merchants selling digital goods – are attributable to identity theft, according to LexisNexis Risk Solutions.

IntSights and Riskified found in a joint Retail & eCommerce Threat Landscape Report studying hundreds of thousands of online purchases that there was a 297% spike in the number of fake retail websites designed to phish for customer credentials from July to September in 2018 over the year prior. Cyber criminals are increasingly targeting retailers and their customers through digital social channels as retailers leverage those channels for increased revenue opportunities.

Read the full report to go behind the scenes on eCommerce fraud, the underground stolen credentials economy, and the illicit credit card credentials trade.

How did the order look to fraud managers?

We mentioned earlier that Kasper Gleason placed his order at 1:49 a.m. on Nov. 23, 2016. That wasn’t the only order he placed. One minute later, he placed the same order again, with no details changed. Six minutes later, another click. At 1:58 a.m., Gleason placed his final order for that day, again with no order details changed.

These early morning Nov. 23, 2016 orders were the first “Joseph Tanner” had ever placed with eCards. A new eCards account for Joseph Tanner was created just a day earlier on Nov. 22, 2016. While that’s not a guaranteed sign of fraud, orders under new accounts and by new customers often catch fraud managers’ attention.

The card ending in 2527 had a zip code match with the Webster, NY billing address and a New York state phone number. As mentioned, the order was placed using a T-Mobile Android mobile phone, reporting a Seattle IP address. No proxies or VPNs were used to try to mask the IP address. The delivery email address for “Kasper Gleason” was [email protected], with the Swiss and German email client. Somewhat random email handles such as kgs337373, are generally riskier than an address such as [email protected] or [email protected]. It makes sense. Fraudsters operate at scale and need a lot of email addresses, so they use free services and create them haphazardly, looking quickly for addresses that aren’t already in use.

A fraud manager reviewing this order or this series of four order attempts in a vacuum, might struggle to make a decision. There are some suspicious markers but no context to use in making a decision. However Riskified’s robust database and behavioral analytics expertise built on years of partnership with over 1,600 merchants, allowed eCards to instantly vet these questionable details with accuracy, correctly declining all of these orders.

In our experience working with leading gift card and other digital goods merchants, we have learned that gift-card buying in the wee hours of the morning is a highly risky purchase. Fraudsters schedule these orders hoping that merchants with manual reviewers are on their off-hours with relatively lax fraud management systems in place overnight.

More importantly, Riskified’s elastic linking technology cross-checked Joseph Tanner’s card number, address, as well as Kasper Gleason’s email address against historical data in our system in microseconds. There had been no legitimate orders by Tanner with the credit card 2527, nor has he shopped on IP addresses outside of New York state. Lastly, the fact that Gleason tried to place the same order four times in ten minutes shows Gleason was not so sophisticated. Not changing any of the information, not trying to scrub his location by using a proxy server, and the short time interval within which he placed the orders, make clear that Gleason clicked ‘check out’ multiple times in hopes that one of these orders would go through.

We see this type of behavior often among fraudsters trying to test a given merchant’s fraud-review system. These fraudsters may be amateurs trying their luck or more sophisticated fraudsters doing advanced research for a more elaborate hit, such as a botnet attack, later on. The fact that the credit card Gleason used – Tanner’s – is a widely available free sample, lets us conclude that Gleason was more of the former than the latter.

To this day, we still see as many as dozens of failed fraud attempts using variations of Tanner’s name and the 2527 card number across the 1,600+ merchants with which we work. Each of these attempts help us and our system get better educated about the types of data fraudsters are using, and keep improving our technology to prevent attacks.

Keeping up with fraud practices and tools

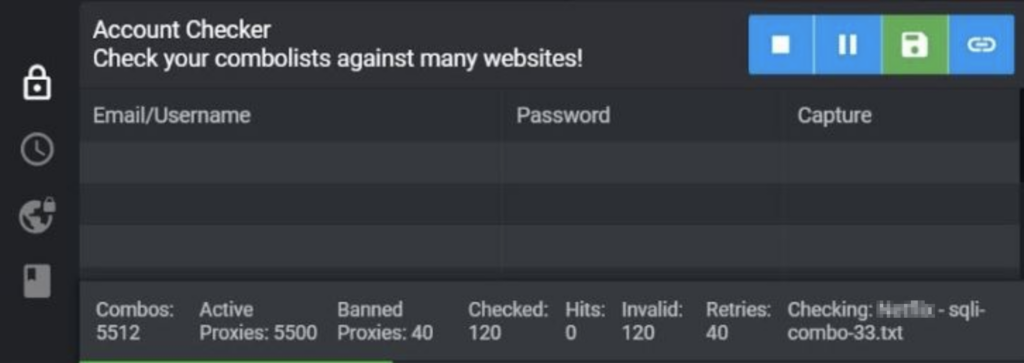

Dark web trends and tools evolve constantly. In order to maximize their take, fraudsters use sophisticated, automated, and tailored tools to commit fraud against retailers. One example is “account checkers.” They automatically work through a roster of breached username and password pairs, or credential stuffing lists, to inject each of them into the login form fields and systematically cross-check whether any of them will unlock fraudulent access to user accounts with retail sites. These types of tools produce a big list of valid accounts on the retail site called “hits,” which the fraudster can then use as he pleases. The checkers have configurations that are customized to circumvent unique characteristics and defense mechanisms of each merchant’s website.

Auto-buying bots are another type of automated tool that hackers frequently use. These bots were originally developed to buy goods on legitimate sites in accordance with predefined rules. Don’t want to lose that eBay auction for a coveted watch that’s scheduled to end at 3:00 a.m.? That’s where an auto-buying bot comes in. But what’s to stop a fraudster from exploiting stolen credit cards at scale with such a tool?

It’s a no brainer for fraudsters to quickly re-engineer these legitimate tools for pernicious use. These tools allow criminals to automate the entire fraud cycle, from stealing credit cards details to committing big, sophisticated, fraud attacks with zero manual intervention required.

Mitigating the effect of these tools and techniques is hard. To keep up with automated tools modified specifically for your site, you need a system that can adapt to the constant evolution of fraud attacks.

How to minimize, monitor, and manage fraud

Like in sports, managing card-not-present fraud requires both good defense and good offense by combining fraud management and external reconnaissance tools. Our advice for merchants is to stick to these five rules each.

Good offense = smart balance between fraud reduction and customer retention

- Remove static or rules-based filters and blacklists

- Don’t rely solely on matches when evaluating orders

- Be careful of adding friction and turning legitimate shoppers away

- Look for a fraud solution that scales with your growth

- Adjust your fraud approach to fit how your customers shop

Good defense = Keeping pulse on an ever-changing landscape

- Monitor social media for fake accounts, unauthorized product ads, and phishing scams

- Regularly update customers on authorized contact channels for support

- Monitor the dark web for new hacker tools

- Watch your retail website carefully, especially pages that require credit/personal details

- Control and limit access to company databases using multi-factor authentication

For specific guidance on managing gift card fraud, be sure to check out our special report as well as our infographic.

To conclude…

The golden age of eCommerce is just beginning: online sales account for only 12-13% of total retail sales worldwide. Fraudsters are constantly innovating to try to exploit merchants, especially those busy optimizing their omnichannel strategies. But there are no reasons to panic. Getting educated on the step-by-step of eCommerce fraud is an excellent start. Up next is partnering with a time-proven, revenue-maximizing, end-to- end solution. Request a demo or read more at our Resources Lobby.