The Not-So-Obvious Costs of Marketplace Fraud

Online marketplaces have always encountered fraud from both ends of the transaction. Sometimes, their users are the victims – buyer and seller accounts are vulnerable to takeovers and card-not-present (CNP) fraud. Other times, users are the ones stepping into the fraudster role, deceptively filing chargebacks or publishing deceptive listings.

The days of just traditional fraud are long gone – we’re living in a sophisticated fraud landscape where both buyers and sellers are gaming the system. And with global online marketplace growth increasing every year, these eCommerce platforms are experiencing new types of fraud at a rapid pace.

Marketplace fraud teams are actively working to protect against known and emerging types of fraud, but some fraud tactics aren’t as clear-cut. Visiting forums on both the dark web and the clear one uncovers endless opportunities for fraudsters big and small.

The evolving framework of marketplace fraud

From Etsy to Alibaba, global online marketplaces are no stranger to hacked accounts, card-not-present (CNP) fraud, and chargebacks. But how do these bad actors obtain the information needed to make a fraudulent move? Let’s dive a bit deeper into each to reveal what’s happening under the surface.

Accounts as a product

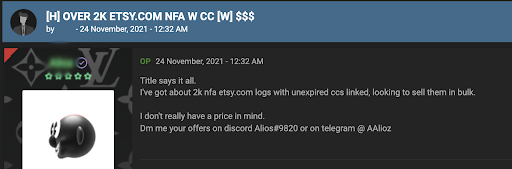

Most people don’t think of their online store accounts as something that’s worth a lot on its own, but for fraudsters, they are valuable commodities. People who commit accounts-as-a-product fraud will obtain customers’ login credentials and sell them to the highest bidder. The fraudsters who sell this information will differentiate between accounts that are not fully accessed (NFA) or fully accessed (FA). When an account is designated FA, it means the fraudster has login credentials to the marketplace account AND the personal email address of the legitimate account owner. This is highly valuable to fraudsters – using a legitimate account can fool the marketplace’s detection systems. Accessing the victim’s inbox lets them receive the order confirmation without their knowledge.

Another form of accounts-as-a-product is selling access to long-term marketplace seller accounts. These are jackpots for fraudsters. They can post fake listings and will be more likely to collect money since more customers trust well-established sellers. The cherry on top – these accounts often hold funds that the fraudster can cash out, or at the very least, access to customer credit card details for further gain or to sell to other fraudsters for a profit.

Sellers buying services

Competition for business on marketplaces is high and sellers rely heavily on user-generated reviews for growth. As a result, sellers are increasingly turning to paying for fake reviews. Sometimes fraudsters create a fake account to post the review, and other times, fraudsters use a hacked account, which increases the legitimacy of the posting. These fake reviews impact the rating of the abusive seller, but they also negatively affect any seller who doesn’t game the system. The result is an unbalanced and uncontrolled environment that may alienate good sellers and damage the reputation of the marketplace.

Buyers buying services

Some marketplace shoppers will pay external fraud services to facilitate a full refund for their purchase. One method, as seen below, asks the customer to initiate a return and then generates fake tracking numbers to help the customer capture their refund without actually sending any item back. From this example, we see that some “best” practices include limiting the number of items and their cost, and only targeting large sellers to make the refund request seem more legitimate. Customers may pay a fraction of what their items cost for this service, making it a very cost-effective service for savvy, fraud-leaning shoppers.

Abusing the rules of conduct

Now that we’ve established the nuanced ways that buyers and sellers are cheating marketplaces and their law-abiding customers, let’s see how far the domino effect of these fraudulent moves extends. The nature of online fraud behavior is that fraud typically leads to more fraud. For example, when a marketplace account is hacked, its stored information can be stolen, and it can be used to facilitate a variety of CNP fraudulent activities. But it can also be sold to abusive marketplace sellers to create fake, but seemingly legitimate, reviews for them. The damage to that marketplace’s brand and bottom line is compounded.

Sellers paying for fake reviews abuse the rules of conduct. Even if their goal isn’t to scam potential customers, they just want to pull a fast one on the marketplace by any means, and this isn’t the only way they go about doing it. Sellers on sites like eBay may create fake accounts to drive up the bidding price for their own gain. Pushing legitimate buyers to bid more can lead to higher revenues for that seller. It may not fall under the exact definition of fraud, but everyone would agree it’s not quite right either. And when such incidents are exposed, they drive a wedge of distrust between marketplaces and customers.

The bottom line

Fraud never happens in a vacuum. Marketplaces are ecosystems ripe for abuse – and it comes at great costs. Instituting stricter decisioning rules on online transactions may keep bad actors at bay, but will also lead to more legitimate customers getting declined. Plus, complaints about hacked accounts, refund requests, and other fraud-related problems can inundate customer service teams and lead to negative customer experiences that turn good customers away. To tackle obvious and not-so-obvious forms of fraud, marketplaces need accurate, machine learning-powered solutions that know fraud trends and evolve with them.

This blog is based on research by Riskified data analyst Ufaz Kaufman.